My experience taking a self-administered sabbatical

A version of this essay was originally published in 1727 Magazine.

This is a long essay. The full length might not appear in the email. If this happens, you can click here to read the full essay on the website.

If you haven’t already, please subscribe to my newsletter. It’s free! And you can easily unsubscribe if you don’t like my writing. What do you have to lose?!

I left my job nine months ago.

Since then, I’ve been traveling, writing, and pondering my purpose on this big blue-green marble. I’ve sojourned in ten different cities, published a collection of poetry, and thought a lot about how to live a good life and what role work has to play in that.

When people ask me what I’m doing, I have a hard time explaining. I usually say something like, “I’m taking a break from work.” I get mixed reactions.

Strangers seem to make assumptions about the reasons why I’m not working. My relatives tell me I should get a job; they imply it with raised eyebrows if they don’t say it explicitly. My friends congratulate me; some say they wish they could do the same thing. In most cases, I think they could if they really wanted to.

Tim Ferriss, author of The Four-Hour Workweek, might say what I’m doing qualifies as a “mini-retirement.” In school, they would call it taking a “gap.” In the working world, “sabbatical” seems to be the more common term. Technically speaking, I’m neither employed nor unemployed; I’m just “not in the labor force.”

Out of those terms, I think “sabbatical” is most accurate. However, it’s still not perfect because it usually refers to an employee being granted permission by their company to leave and then return to the same position after their time off. In my case, I left my previous job with no intention of returning.

My purpose in writing this essay is not to prove any particular point or to convince anyone that they should or should not take a sabbatical. I’ll explain why I decided to take a sabbatical in the first place, narrate my experience so far, and share some of the lessons I’ve learned.

Graduating from college and entering the labor force.

When I graduated from college in 2017, employment was the next step on the traditional path—go to school, then get a job. Even if I would have rather done something else, I didn’t have much of a choice. I needed money for basic expenses like groceries and rent. And, like 65% of college graduates, I had student debt.

In 2017, the average graduate owed $28,650. What I owed was slightly more than that amount—enough that it would have been an unwise financial decision to allow the interest to accrue, which would have been ironic, considering I had just received a four-year degree in finance.

On June 5th, two weeks after graduation, I started as an Account Executive Trainee at a tech company in San Francisco.

I worked in San Francisco for two companies for the next four years—a public company with almost 10,000 employees and a startup with less than 50 employees.

At the public company, I started as an Account Executive, making a minimum of 80 cold calls per day, selling advertising to small businesses. In the beginning, I was terrible at my job—like, really bad. But thanks to my patient manager and helpful senior salespeople, I eventually became one of the top-sellers at the company and earned a promotion to Sales Manager. I managed several teams of AEs for about a year before leaving the public company to join the startup.

At the startup, I joined as the first salesperson, then hired a team and grew into a Head of Sales role. We achieved tremendous growth, raised a Series A round of funding, and moved to a bigger office. Then San Francisco issued the shelter-in-place order due to the pandemic and our entire staff transitioned to remote work. At that point, a lot changed. We adapted well as a company and continued to grow, but I personally struggled with the transition to remote work due to the lack of work-life separation while spending all of my time inside a 500-square-foot studio apartment.

In March of 2021, shortly after my two-year mark, I resigned from my position at the startup and haven’t looked for a new job since.

Why I decided to take a sabbatical.

By the time I left the startup, I had finished paying off my student loans and even managed to put away enough savings to cover my living expenses for a couple of years—longer, if I lived frugally—with no other source of income.

Having temporarily satisfied my original financial need for employment, I was fortunate enough to be able to ask myself, “Do I want to go back to work?”

My answer: no, for two reasons.

First, I was burned out. Second, there were other things, besides work, that I wanted to spend my time on—traveling, writing, and giving myself the space to see what else would get sucked into the void that was previously filled by my job.

Even if I hadn’t burned out, I think I still would have taken a sabbatical soon after becoming financially capable of doing so.

I’ve been planning for early retirement ever since I took a personal finance course during college and realized that waiting until I’m 65 years old wasn’t the only option. The basic idea was that I would live a hyper-frugal lifestyle to save money until I could afford investments with high enough returns to pay for my annual living expenses. (I didn’t know at the time, but there’s a movement known as FIRE, which stands for “Financial Independence, Retire Early,” that subscribes to a similar, if not the exact same, financial philosophy.)

My annual expenses fluctuate around $30,000. If we assume the 4% “rule of thumb” for returns, I need to save $750,000 ($30,000 divided by 4%). Or, if we assume that I can live more frugally (annual expenses of $20,000) and invest more successfully (annual returns of 8%), then that number shrinks to $250,000. That seems like a cheap price tag for financial freedom, doesn’t it?

My original idea was to sprint to this “I can retire now” number as fast as possible. But I’ve since changed my strategy.

Because what if I die before I save that much? Statistically, this is unlikely, and I have a good chance of surviving. But still, I’d rather take small bites of the fruits of my labor along the way rather than wait to gorge myself at the very end, especially since there are some things that are better enjoyed with a young body and mind. I don’t want to wait until I have a bad back and achy joints to jet ski in the tropics or climb Mount Everest.

Burnout wasn’t the driving force behind my decision to take a sabbatical, but it was the initial push I needed to make a change, to do something I’d already been thinking about doing for a while—just sooner. As coincidence would have it, I burned out around the same time that I finished paying off my student loans and had some savings left over.

The worst-case scenario wasn’t that bad.

I did have a couple of concerns about exiting the labor force, even if it was just for a short period. The possibility crossed my mind that a “gap in my resume” would stunt my career growth. I also considered that I wouldn’t be making any financial progress toward my “I can retire now” number.

At the very worst, I thought, I’d come a long way in the first four years of my career and, if I had to, I could start over and do it again—probably in half the time, given the experience I’d gained and the skills I’d learned.

And that would be the worst-case scenario.

I thought it was unlikely that I would have to restart my career from an entry-level position, and I figured I could “tell the story” of my sabbatical in a way that future employers would understand. And any loss of retirement savings from one or two years of foregone wages would be marginal in the long run.

Once I realized the downside risk was limited, my mind was made up.

Transitioning from work to sabbatical.

Initially, leaving the company was stressful. But once I’d reassigned my responsibilities, said my goodbyes, and signed the paperwork, I started to feel relieved.

The transition from my last day working to my first day not working was both sudden and subtle. It was sudden because my work flipped off like a switch—one day, I was working, and the next day I wasn’t. It was subtle in the sense that not much noticeably changed. The only obvious change to my day-to-day life was that I opened my laptop one day, and the next day I didn’t.

My work didn’t exist outside of my computer. All the emails, instant messages, saved files, and spreadsheets comprised a separate virtual world. When I closed my laptop at the end of my last day, it was like I left that virtual world and took an interplanetary flight back to the real world. I put my computer in a cardboard box and shipped it back to the company, and that was that.

Traveling to cool my burn(out).

After being cooped up working from home for a year, I yearned to travel—to get out and see something other than the walls of my apartment, to take more than two and a half steps from my desk to the bathroom, to do something other than sit and stare at a computer.

First, I had to take care of some “life admin” chores (checking if I needed to roll over my 401k, setting up my health insurance). Then I started mapping out my travel plans. I made arrangements with friends, bought plane tickets, and packed a backpack for an indefinite amount of time that I planned to spend sojourning in various cities, mainly on the west coast.

From April to September, I lived out of a backpack and spent time in San Francisco, San Diego, Cabo, Big Sky, Nashville, Gatlinburg, Elk, and Leavenworth.

For the first three months of my travels, I relaxed. I lay on the beach in San Diego, took too many tequila shots in Cabo, and read a novel in a cabin in Big Sky. I wrote this poem (“Shy Star”) when I woke up early one morning in Big Sky to watch the sunrise behind the mountains:

I arrived early

For the sunrise showTook my seat

On the deckAnd waited

In the darkFor the cloud curtains

To partBut the mountain stage

Remained emptyWhile the star

Hid below the horizonLike a shy child

Who forgets every nightHe is the sun god

And must muster againThe courage

To shine

By the end of June, I had gotten what I needed from my travels: I was re-energized and not feeling burned out anymore. At some point—maybe after repacking my backpack for the twentieth time—I was ready to stay put in one place for a while.

I also had a renewed motivation to be productive again, and I was curious to see what channels the streams of my natural creative energy would flow in. Liberated from working as an employee for a company, I had the freedom to set my schedule and the autonomy to work on personal projects that I’d been keeping on the back burners.

The main personal project that I wanted to move to a front burner was my writing.

Writing is what I love to do.

I started writing as a sophomore in college. I remember the exact day. It was wintertime in South Bend, and we were running around the frozen lake on campus. There were five of us bounding along the trail, billowing clouds of condensation like a train of steam engines.

One of my classmates at the front of the line shouted back to the rest of us, “What’s one thing you guys want to do before you die?”

When it was my turn, I shouted back, “I want to write a book.”

After I said it, I thought to myself, what am I waiting for? I started writing immediately when I got back to my dorm room. Well, not immediately. I had to wait for my fingers to thaw.

I haven’t stopped writing since. I skipped class to write. I wrote while I was working. I wrote during my recent travels. I’m writing now, literally.

While working, I wrote early in the morning, late at night, and on the weekends. I was never writing as much as I wanted to because of my day job, but I was happy enough as long as there were some gaps in my working schedule when I could write. There was even a sort of synergistic balance between my rigid working life and my creative writing life.

During my last job, however, that balance broke down. As I was getting busier and busier at work, I was writing less and less.

At first, I was still writing new material, but I fell behind on editing and organizing. Then, at some point, all my unorganized drafts began to feel like a glut, like a clog in my arteries. Eventually, I was barely writing anything new because it felt like I was just throwing more dirty clothes on top of an already-huge pile of laundry.

A sabbatical was a perfect opportunity to take all my unfinished drafts to the laundromat.

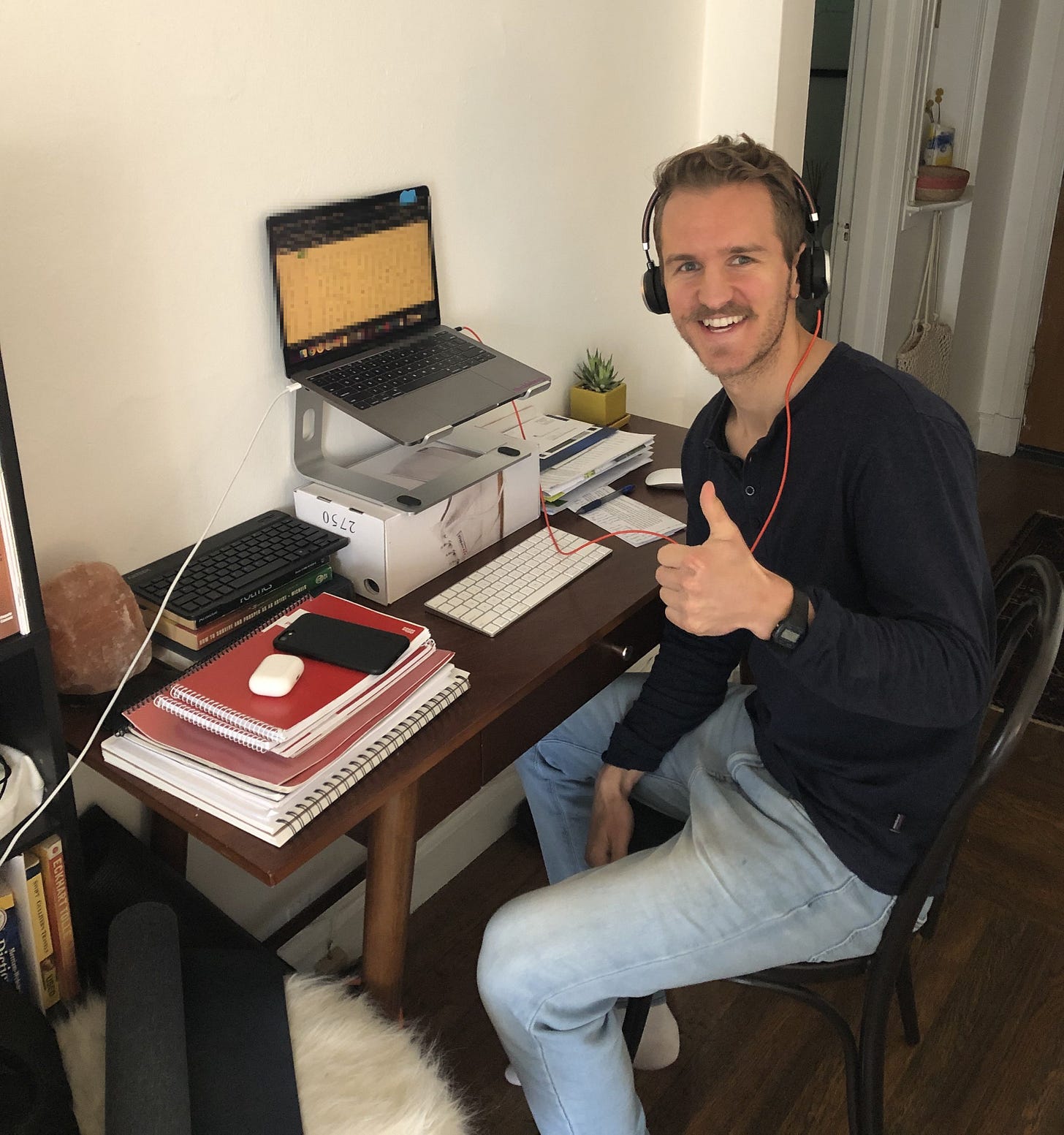

In the dining room of my girlfriend’s apartment in San Francisco, I set up an improvised standing “desk” (I set my laptop on the most ergonomic shelf in the hutch) and started sifting through the backlog. In September, I published a collection of poetry, The Art of Sidewalking.

Some of my favorite poems in the collection were written during my sabbatical.

Back home in Kansas.

While I was traveling, everything was moving fast. I was relocating to a new destination at least once a month, and when I wasn’t sojourning somewhere, I was with my girlfriend in San Francisco, staying busy with city life. Whenever I had a spare moment, I was writing, which, at the time, mostly meant editing my poems and organizing them into a book.

Now, things have slowed way down. I’ve finished my poetry collection, and I’m back in the suburbs of Kansas City (where I grew up), living in my parents’ basement. On the plus side: it’s beautiful this time of year in Kansas, as the leaves change colors on the trees. On the minus side: I’m living in my parents’ basement.

Grappling with boredom as a recovering workaholic.

After 19 years of education and four years in the workforce, this is the longest period of time since before I was three years old that I haven’t been either in school or employed.

On my journey through the education-to-employment pipeline, I learned the best practices for optimal productivity, was indoctrinated with the values of work-obsessed American culture, and grew accustomed to having a full schedule and an endless to-do list.

Now, on sabbatical in a sleepy suburb of Kansas, there are times when I don’t know what to do with myself.

When I do feel bored, it doesn’t last longer than a few minutes. I’m too good at coming up with things to do. Even without a job, I’ve been able to create plenty of work for myself. But there are still times, usually right after I’ve completed a task, when I have to stop and ask myself, “Okay, what should I do now?”

It’s not always an easy question to answer.

What do you do when there’s nothing to do? When nobody’s telling you what to do. When the only event on your calendar is a dentist appointment in two weeks. When you could (if you wanted to) sit on the couch, watch TV all day, and get food delivered to your doorstep.

While I was working in the city, the answer to this question was always obvious. Weekdays were nonstop—commute, work, gym, commute, eat, sleep, repeat. And weekends were spent trying to cram in as much leisure as possible (seems paradoxical, I know) before the coming workweek.

Now, the answer is much less obvious. I continue to work on my writing and I’ve started several side projects—coaching the debate team at my old high school, sending snail-mail letters to my friends, helping a former colleague with his startup, learning about crypto. But there are still brief moments, especially in the evenings after I’m done with my work for the day, when I stare at the wall and blink.

I’ve been making an effort to embrace these moments.

Even when the boredom borders on being uncomfortable (and every so often tips toward existential anxiety), I resist the urge to fill the void—to turn on the TV, to look at my phone. Instead, I try to sit with the quiet stillness and mull it over, to be mindful of my sensory experience, to become aware of the tingling sensation of aliveness in my hands and feet (a technique I learned from Eckhart Tolle’s book, A New Earth).

But I often fail.

Nine times out of ten, I’m not able to rest in silence for more than a few minutes before I get distracted and start to busy myself with a task or a train of thought. Sometimes I just go from one thing to the next, without even noticing the moment of peace in between.

This is an area of my life where I want to improve. I want to be able to relax comfortably in quiet stillness, to find peace in idleness. Because I believe that, in the emptiness within myself that becomes a sucking vacuum in these moments of boredom, there are important lessons for me to learn.

Most of the times that I fail to sit in silence, it’s because I can’t refrain from opening my laptop. Work is my weakness. Some people binge-watch Netflix shows. I scroll through my Evernote in search of a rough draft to edit.

To an extent, this seems healthy: being creative brings me joy and it’s probably better than vegging out in front of the TV. But at a certain point, it becomes toxic: when I consistently prioritize my work ahead of other important parts of my life.

Currently, I’m prioritizing my work ahead of my mindfulness practice. Before, I prioritized my work ahead of my relationship with my girlfriend. And before that, when I was working for the startup, I prioritized my work ahead of my health.

Why I’m addicted to work: a theory.

It’s difficult to recognize the toxicity of workaholism in our American capitalist society that values productivity above all else, which is likely part of why I developed my addiction to work in the first place.

I have a box in our attic full of honor roll certificates, debate medals, and wrestling trophies from when I was growing up. I thrived on approval from my parents and acclaim from my teachers. Moreover, I thought I was winning the game. They told us if we earned good grades, were accepted into a top college, got a high-paying job, and made a lot of money, then we would live happily ever after. And I believed them.

It wasn’t until I was already halfway through playing the game, while attending college, that I realized going on to get a job and make money wasn’t the way to win the game, or at least that it wasn’t the only way. But by then, it was too late. I had already spent my most developmental years training to be an overachieving member of the workforce.

Outer work vs. inner work.

I’ve taken steps to redesign my lifestyle, e.g., taking this sabbatical and planning for early retirement. But I’ve recently realized that it goes deeper than just changing the surface-level situation of my life. Because I still inhabit a body and mind that are built to work. And even when I stop working, I will still inhabit this body and mind.

Taking a sabbatical has been like a test run for not working, like running a warm-up lap for the retirement marathon. It’s allowed me to observe how I behave without either school or work as a constant distraction.

What I’ve discovered about myself: I still find a way to keep working. I quit my job, yes. But other than during the months that I traveled, I never really stopped working. I just changed what I was working on. Even when I was traveling, I was still working on my writing whenever I could.

My toxic work habits didn’t go away just because I left my job. I realized this as I was working on my collection of poetry. There were days that I would wake up with a new idea, skip my morning routine, and immediately open my laptop. If I was making good progress, I skipped lunch. Then, sometime around four or five in the afternoon, my low back would start hurting and I’d realize that I was starved and dehydrated. It was déjà vu from my time working at the startup.

This forced me to recognize that, ironically, I had more “work” to do. But it was different work. Not school work, sales work, or writing work (outer work)—but work on myself (inner work).

I’ve only just started, but these are some of the realizations I’ve had from the inner work I’ve done so far: burning out at my last job was, at least partly, my fault; I deprioritize my relationships when they detract from my work; my self-esteem is dependent on me producing work that is well regarded by others; and I seek love and admiration as validation for my work.

Alas, I’ll probably go back to (outer) work soon.

Suppose I already had an amount of money greater than my “I can retire now” number. In that case, I’d extend my sabbatical indefinitely because I would rather continue to spend my time writing and doing my inner work.

But the reality of my financial situation is that I need to earn more money at some point. It’s like I’m a player in a Maslowian game, and I’m still stuck on the lower levels of the hierarchy of needs.

I have enough left of my savings that, based on my current rate of spending, I could extend my sabbatical for at least another year. But then, by this time next year, I will have spent almost all of my savings.

Eventually, I’ll have to find another job anyway, and I’d rather not spend all my savings, so I’m leaning toward returning to the working world sooner rather than later.

But I’ll continue to take sabbaticals.

Henry David Thoreau took one of the most famous sabbaticals of all time. In 1845, he borrowed an axe, went out into the woods, cut down some trees, and built his own house on the shore of Walden Pond in Massachusetts, where he lived for two years and two months.

To earn his independence, Thoreau worked for six weeks out of the year as a day laborer. He lived alone in the woods for the rest of the year and had free time to “study.”

I’m not as hardy or resourceful as Thoreau. Perhaps I have the physical ability to work as a day laborer, but I certainly don’t have the carpentry skills to build my own house. And I’d get lonely out in the woods by myself. Still, I plan to achieve something similar to Thoreau—an independent lifestyle with free time for my “chosen pursuit”—by different means.

My plan to earn my independence is to return to work and continue earning wages, taking sabbaticals at opportune times, until my savings surpass my “I can retire now” number.

Depending on my living expenses and investment returns, it will take me between four to eight more wage-earning years to save that much. Either I’ll work for four years, take a sabbatical, and then return to work for another four years. Or I’ll work for two years, take a sabbatical, work for two more years, take a sabbatical, and so on until I can retire.

Because I value the freedom to choose my work.

In his book Walden, Thoreau writes,

“As I preferred some things to others, and especially valued my freedom, as I could fare hard and yet succeed well, I did not wish to spend my time in earning rich carpets or other fine furniture, or delicate cookery, or a house in the Grecian or the Gothic style just yet.”

I’m not taking sabbaticals and saving for early retirement because I don’t like to work. Rather, I’m doing this because, like Thoreau, I value my freedom. Instead of working beyond the point when I have ample means for my survival, I choose to work on what I want, regardless of how much money it makes. Right now, that’s my writing and my inner work.

Thank you to Lyle McKeany, Mark Koslow, Shivani Shah, and Harris Brown from Wayfinder for their editing help.

Thank you to my good friend Cornelius McGrath for inviting me to write this essay for his magazine, giving me the motivation to process and put down in words my unresolved thoughts and feelings about this transitionary period in my life.

1727 Magazine is a quarterly publication by Everyday Entrepreneur. The focus is on “evergreen” first-person stories, conversation, and ideas. This essay was included in the third issue of the magazine.

Life update: I moved to Denver at the end of December. I’m living in a building called X Denver that is designed for coliving and community. And I’ve started the job search process (I’m applying mostly to sales and business development positions at crypto companies). If you’re in Denver or have connections in the crypto world, send me a message!

If you haven’t already, please subscribe to this newsletter to get my writing sent to your email inbox. Over the next couple of months, I’m going to be writing long-form essays about work (as well as whatever comes to mind, per usual).

Last but not least, please click the heart and leave a comment.

My favorite part about writing is how it can create dialogue. And I believe this essay brings up issues that are timely to discuss. There’s obviously something going on that’s causing trends like “The Great Resignation.” I’d love to hear your thoughts.